You may have heard of a method called “cold crashing” originally used for wine brewing. For wine, this process has been used for centuries to precipitate the yeast and tartaric acid crystals, but cold crashing has a slightly different function for most mead brewers.

Cold crashing is the process by which mead at the end stage of primary fermentation is cooled to a significantly lower temperature (typically 4°C or 40°F) to shock the yeast into halting its metabolic activity.

This will, with some luck and depending on the yeast strain, stop active fermentation completely, resulting in some residual sugar remaining in the brew and complete precipitation of the yeast for a sweeter, clearer, mead!

Some people prefer cold crashing because it stabilizes the final product, and others do it to retain a degree of sweetness in the mead.

The process is surrounded by a lot of anecdotal evidence to it, but I will try to summarize personal experiences as well as some actual research that has been done in this article.

However, it is clear that the cold crashing process is highly dependent on the type of yeast (e.g. wild or commercial, wine or beer yeast etc.) and the point in the fermentation process where the cold crashing is performed.

What is cold crashing a mead and why do it?

Cold crashing is the least intrusive way of stopping a mead fermentation, and while other methods exist (that I will get into later in this text), cold crashing is probably the best way to preserve the flavors and clarity of your mead.

The lower temperatures will retain a number of beneficial volatile compounds as well as prevent the metabolisms resulting in unwanted flavor compounds.

When searching through people’s experiences with cold crashing, these are the most common benefits that are mentioned:

- It stabilizes the mead and stops fermentation.

- It results in more residual sugar for a sweeter mead.

- It results in better clarity (fewer yeast cells, proteins, and other solids).

- It removes some undesirable flavors.

- It may reduce the amount of acidity.

- It can reduce the amount of tannins.

- It reduces the harshness of the mead.

- It precipitates dead yeast cells.

- It can reduce the amount of fusel alcohols.

- It reduces the amount of diacetyl (butterscotch/butter flavor).

- It removes acetaldehyde (cheesy flavor).

- It results in a softer, rounder taste overall.

I could add more to this list, as cold crashing is highly praised in the mead community, but we would get into very specific anecdotal cases that are not widely supported.

But in fact, I can myself confirm many of these points from my own mead making. Especially when using wild yeast for my brewing, I can taste a huge difference when cold crashing the fermenting vessel at late-stage fermentation.

Does cold-crashing Mead stop fermentation?

Yes, the whole idea of cold crashing is to stop the fermentation process without using heat or chemicals. In this way, you obtain a clearer and more aromatic mead.

Other ways to inhibit the yeast is to add sulfites or benzoic acid compounds (potassium sorbate). However, this is not a guarantee that the yeast will be completely dead and if it revives on the bottle the effect can be devastating (broken glass…).

The safest, but also more advanced and expensive, way to stop fermentation before time is to filter out the yeast as most modern breweries will do.

Another way is to pasteurize the mead to kill off the yeast before it would naturally dies from starvation. This, again, is a delicate process that will come at some risk of bottle explosions later on if not done correctly!

Normally the live yeast left in the brewing mead (even if it seems to be latent) will actively perform secondary fermentation and carbonate your mead naturally on the bottles.

When should you start cold crashing mead?

Most people cold-crash their brew at late-stage fermentation but before all the sugar is gone. This stage will typically take around two weeks to reach and the brew will have a specific gravity between 0.995 and 1.030.

But these times and numbers will vary depending on your sweetness and flavor goals, types of yeast, honey, brewing temperature used etc.

Most people, however, do not cold crash before going below SG 1.030 as it gets harder to cold crash the more sugar is left and you would like some alcohol and flavors to be formed before halting fermentation.

A final SG of around 1.020 typically means alcohol (per volume) of at least 4.5% for a good sweet starting point, but it really depends on how much honey you have added to your mead!

The best thing you can do to determine when exactly to cold crash your mead is to taste it as the fermentation goes along!

Simply take out a small sample every day and judge whether it is too sweet or too dry for your liking.

When the mead reaches the desired (minimally tolerated) sweetness, you should start the cold crashing procedure.

At what temperature do I cold crash mead?

Most people cold crash their mead at normal refrigerator temperature which is 40° F (4° C).

Personally, I have also just put my mead outside in the late fall when temperatures drop below 60°F and left it for a few weeks until the temperature reached around 30°F. This was always sufficient to stop wild yeast fermentation when the SG was below 1.010.

However, scientific studies do seem to suggest that the colder the better. But only to the point of freezing, which would result in the shattering of most storage containers!

In theory, below the freezing point can work really well, but it is also going to rupture the yeast cells resulting and a lot of off-flavor compounds being released into your mead!

So I would recommend cold crashing your mead at maximally 50°F, and for most people at 40°F due to the practical overlap with most fridge temperature setpoints.

How cold is too cold for cold crashing?

Only the container and your intended use of the brew, later on, matter for what the minimal temperature of cold crashing can be.

If you store your brew in a glass container, it may break below the freezing point of your mead. However, the freezing point of your mead will depend on the sugar content left at the time of cooling.

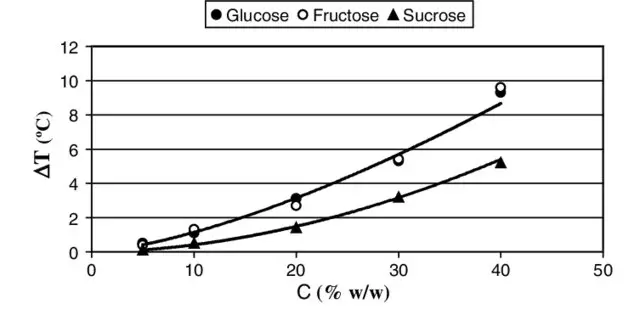

For mead, the sugars are mostly fructose and glucose, so this will have a more dramatic impact on the freezing point than that of sucrose.

Because more sugar in the brew will lower your freezing point, a sweet mead (crashed at a higher specific gravity) will tolerate a lower temperature without forming ice crystals that may disrupt the taste and rupture the storage container.

However, do not expect big differences when the fermentation is near its end!

For example, if your mead has a specific gravity of 1.040, you have 100g/L which will be around 10% and thus reduce the freezing temperature by maximally 2°C leading to a new freezing temperature of -2°C or 28°F.

However, the formed alcohol formed at that time will also influence the freezing temperature.

For example, if 15% alcohol had been formed in your mead so far, it would reduce the freezing temperature an additional 8°C leading to a new freezing temperature of -10°C or 14°F!

In that case, you could leave it out on even the colder nights where I live…

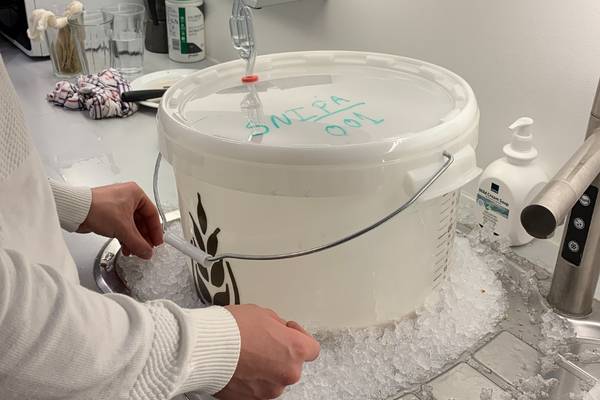

Can I cold crash my mead without a fridge?

Yes! there are numerous ways to cold crash without a fridge, but it will require a bit more creativity and/or luck!

One way is to simply submerge your fermentation vessel in ice:

Another possibility is to leave it out in the snow. As long as it does not get too far below 32°F it will be alright. Do not leave it outside at night if the temperature drops dramatically.

I leave mine close to the house in a small shed that is somewhat insulated. It tends to keep above 32°F even when freezing outside. Putting some blankets over the bottle can also help stabilize the temperature.

You may also just want to shock it with a “quick” dip in the snow for a few hours, after which you bring it inside to your basement.

The yeast strain matters for cold crashing!

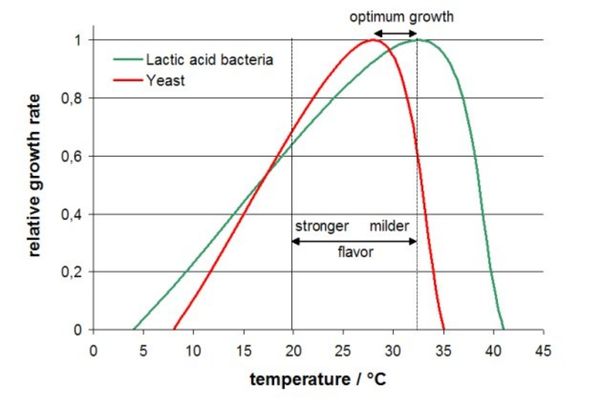

Not all yeast ferment equally, and the temperature spectrum for optimal fermentation varies across strains.

For example, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, commonly used in mead brewing, has an optimum fermentation temperature of around 30°C (86°F), and tolerates alcohol and low pH well. The same is the case for Saccharomyces bayanus, that is also within this range.

These yeasts are not very efficient at lower temperatures and they perform at less than 10% of their maximum capacity at 5°C (40°F).

That is, under ideal conditions of low alcohol, optimal pH, available sugars and nitrogen sources they perform at one-tenth of the optimal performance at 30°C (86°F).

However, if the conditions are suboptimal their growth may halt completely at fridge temperatures.

In addition, several lactic acid and acetic acid bacteria contribute to the fermentation in wild-fermented meads and will also follow a similar temperature-growth curve.

The cold crashing concept has been developed mostly with S. cerevisiae yeast strains in mind, and because these strains grow poorly at lower temperatures, the cold crashing works best for these mesophilic (growing at medium temperatures) strains.

Some yeasts, however, have evolved to tolerate colder conditions and these may be found in wild ferments and are used for brewing lager beers.

Cold-tolerant yeasts such as Saccharomyces kudriavzevii, S. uvarum or S. eubayanus are able to grow reasonably well at these temperatures, but they will not tolerate factors such as pH and especially high alcohol concentrations very well.

Therefore, these strains are not often used in high-alcohol brewing but may be beneficial if you want a sweeter mead with a low/medium alcohol percentage.

Some more cold-tolerant hybrids such as the S. pastorianus used in lager beer fermentations that are derived from an S. cerevisiae crossed with S. eubayanus will ferment well down to around 5 centigrades (45F) and will be to hard “crash” with cold alone.

But not only the temperature matters. The time the mead is left cold and the speed with which the mead is cooled also matters!

How long do I cold crash mead?

The time aspect of cold crashing relates to both the speed of cooling and the time of storage at cold temperatures.

Scientifically, you should cool it down slowly but gradually as this will result in less surviving yeast but also prevent local freezing and allows time for the yeast to settle.

For a 1 gallon (3.7 liters) it will take a good long night (10 hours) to reach the desired temperature range of cold crashing. For larger e.g. 5 gallon containers, it will take longer, but not five times as long!

After the mead has reached the desired temperature, you want to keep it there for at least a couple of days and preferentially a few weeks.

This allows all the flavors to dissolve and for the yeast and other particles (e.g. pectin) to settle.

When no CO2 /bubbles come out of the airlock anymore and the SG has been stable for at least 5 days in a row, it should be safe to rack the batch into a fresh pre-cooled container.

The second racking should then be left at the same, or lower, temperature for another few weeks to make sure the fermentation does not restart. Longer does not hurt, but will count more towards the aging of your mead, which develops its taste further!

You can store it for too long, as the yeast will start to break down and give off bad tastes, however, this will take months to years before you will really notice.

Some people add potassium metabisulfite (campden tablets) and potassium sorbate at this point to keep the yeast from “waking up” again. A combination of these chemicals and cold crashing seems to be the most effective way to stop fermentation without heat or filtration.

This is the best way to make sure the mead is stable, but it will prevent you from performing any secondary fermentation in the bottles later on!

This leads me to the next point – cold crashing and bottling!

The Benefits of Cold Crashing Mead

There are several advantages to cold crashing your mead.

These include:

1. Improved clarity: Cold crashing encourages yeast and other particulate matter to settle out of suspension, resulting in a clearer final product.

2. Reduced sediment in bottles: By making the yeast settle at the bottom of the fermenter, cold crashing can help reduce the amount of sediment in your bottles or kegs.

3. Faster maturation: Cold crashing can help speed up the maturation process of your beer, as the yeast has already settled out, and the beer has been exposed to cold temperatures.

4. Stabilization of flavors: Cold crashing can help stabilize the flavors in your mead, as it reduces the chance of further fermentation or changes in the beer’s composition due to yeast activity.

The Drawbacks of Cold Crashing Mead

While cold crashing has its benefits, there are also some potential drawbacks to consider:

1. Risk of oxidation: When mead is exposed to cold temperatures, it can absorb more oxygen, which can lead to oxidation and off-flavors in the finished beer.

2. Potential for contamination: Cold crashing requires opening the fermenter and potentially exposing your beer to contaminants, such as bacteria or wild yeast, which can spoil your mead.

3. Additional equipment needed: To cold crash your beer effectively, you’ll need a temperature-controlled environment, such as a refrigerator or temperature-controlled fermentation chamber. This can be an additional expense and take up valuable space in your home brewery.

4. Potential impact on yeast health: While cold crashing does not kill yeast, it does cause them to become dormant, which may impact their overall health and vitality. This can be a concern if you plan to harvest and reuse your yeast for future batches.

Should you cold crash mead before bottling?

Yes. Most people cold crash their mead before bottling because the process is harder to control on the bottles and because you will want to get rid of the excess precipitated yeast.

When cold crashing in the carboy or other fermentation vessel, you can more easily take out samples and follow the taste and the progress of the yeast flocculation (yeast collecting at the bottom of the vessel).

However, that being said, there is no reason why part of the cold crashing e.g. after the first racking when the SG has stabilized, cannot be continued on the bottles.

For example, one might rack the mead to get rid of the yeast after a week or two of cold crashing and then bottle directly hereafter.

I have personally tried this process a few times with great success. I have even been able to back-sweeten the mead without restarting fermentation!

I have only tried it with a monoculture of wild yeast so far, so it might not work for more aggressive yeast strains although people report similar results using the Nottingham commercial strain.

The way I do it is to bottle immediately after racking, being very careful not to include visible yeast. I do not add sulfites, benzoate or sorbates.

I add a bit of sugar to each bottle (about 5 grams per liter) and keep it at room temperature for a week or so after which I move the bottles back to the fridge as a type of “second cold crashing”.

Does cold crashing affect taste?

Most profoundly, cold crashing affects the sweetness of the mead as it allows us to stop fermentation before reaching complete dryness. It also retains more volatile organic compounds in the brew.

Most people start their cold crashing somewhere near the dry end of the fermentation though, and not in the beginning.

There are many reasons for this, but the most noticeable ones are that you do not want to stop the fermentation before all the nice alcohol and flavors have formed.

And it is also very hard/impossible to stop a super active fermentation by cold crashing alone!

So the whole idea of cold crashing is indeed to affect the taste of the final product.

But what about other attributes of the taste than sweetness?

Well, from beer brewing we know that the lager owes its clean and crisp taste profile to the fermentation at temperatures below 60°F (15°C). In contrast, lower fermentation temperatures of white wines tend to make them more aromatic!

A low fermentation temperature is known to alter the lipid metabolism of wine yeast and lead to the production of more methyl esters (those that contribute to fruity tastes) and the lower temperatures prevent them from evaporating out of the brew.

Studies conducted on wines have found that the aromas associated with fruits and freshness are produced and retained more at the lower sub-60F temperatures, whereas the more strong floral flavors develop at higher (82°F (28°C) temperatures.

A lower temperature will also lower the formation of smelly compounds like sulfur, which I have written a whole article about here.

So does cold crashing always improve flavors and smell?

I would say so, but it very much depends on your taste! If you simply love a completely dry and complex, perhaps bitter, floral-tasting mead, just ferment your mead to the end at room temperature or above.

But if you want it sweeter, crisper, and clearer, go for cold crashing. Or at least give it a try!

Cold crashing will help you achieve those fruity flavors many people miss in their first attempts to make mead. Aging your mead also helps a bunch, but if the starting product is not good, the final product won’t be either.

The process of basically keeping some unfermented juice left in the brew that hasn’t been touched by the yeast is quite unique and will give your mead a great aromatic lift in my opinion.

The aromatic esters and the sharp acids seem to blend more nicely together when fermentation is not carried all the way to the end.

However, there are no rules for how to make good mead. You’re in charge, and even though the classical mead breweries in Spain and France love to ferment at colder temperatures, you might like a different flavor profile.

In case you have not read my article about the compounds that contribute to the smell and flavors of mead, here is a small summery:

The most important aromatic compounds when it comes to brewing are:

- Esters (they all smell of flowers and ripe fruits)

- Phenols (some smell like vanilla, but many cheesy are musky)

- Pyrazines (the smell of grass, chocolate and vegetables)

- Terpenes (smells of pine wood, spices and lavender)

- Thiols (most smell bad like skunk or fish)

- Organinc acids (sour smells like yoghurt or sweat)

So, if any bad smells are coming from your mead, or any other brew, it is likely to be caused by the thiols (sulfur compounds), phenols or acids present in the brew.

However, as you can see in the table below, there are many different chemical families that contribute to the aroma of a brew – be it mead, wine, beer or champagne!

| Aromatic group | Good smells | Bad smells |

| Esters | flowers and ripe fruits | Artificial, too sweet |

| Phenols | Vanilla, wood, sweet, smoke | Cheese, tar, plastics |

| Pyrazines | grass, chocolate, vegetables | Mushy, green pepper, mud |

| Terpenes | pine wood, spices, lavender | Gas, turpentine |

| Thiols | Dark chocolate, burned | Skunk, onion, smoke |

| Aldehydes | Nuts, fruits, grains, grass | Musty, burned, gas |

| Ketones | Flowers, fruits, cheese | Cheese, nail polish, Acetone |

| Amines | Nope. | urine, dead animals, fish |

| Carboxylic acids | wax, nutmeg, vinegar | Rancid, sweat, sour feet |

These are not single chemicals, but families of many different versions of chemicals. For example, esters are responsible for major smells in almost all flowers and fruits!

The top ones (esters, phenols, terpenes, and ketones) are the ones most affected by the temperature of fermentation as they are the results of fatty acid metabolism and some are very volatile!

Conclusion

Cold-crashing mead is a process used to stop fermentation and preserve the flavors of the mead. The process is highly dependent on the type of yeast and the point in the fermentation process where the cold crashing is performed.

Cold crashing can help you achieve those fruity flavors and that sweetness in your mead.

Cold crashing is a method used to stop fermentation in mead. It is typically done at the end stage of primary fermentation, when the mead has a specific gravity between 0.995 and 1.030.

The process is surrounded by a lot of anecdotal evidence but I hope this article has cleared out most of your confusion and answered your questions about cold crashing mead!

-recipe.jpg)